SiX Principles for Maximizing and Managing Federal Grants

In order to maximize and effectively manage federal grants to state governments, lawmakers can utilize the SiX Principles for State Legislatures, which envisions a values-based approach to how state legislatures can be governments of the people. The following section provides examples of how some state lawmakers and other community leaders have approached intergovernmental collaboration.

About the SiX Principles

The SiX Principles for State Management of Federal Funds is a values-based framework for transforming our federal and state funding process into a more democratic process where more people—particularly those with the lived experience necessary to inform critical policy decisions—are empowered to participate in the budgetary process.

Instead of a specific set of policy recommendations, we adopt a framework driven by a set of principles because every state and legislature is unique. The SiX principles aspire for states to manage federal funds in ways that are more inclusive, accountable and transparent, responsive and effective, accessible and collaborative, equity-focused, and innovative. This model of governance requires state legislators and local advocates to explore new ideas. No single set of policy recommendations will achieve the same transformation across all states, and these principles are not mutually exclusive (many of the examples included in this section advance multiple principles), but rather, are mutually reinforcing.

Importantly, the SiX Principles for State Management of Federal Funds are not a universal cure for the decades-long effort by corporate special interests to shift benefits to the elite few all while divesting in the public programs that serve the many. Rather, these principles represent a critical tool to reimagine American governance at all levels and put power back in the hands of the people.

Inclusive

State legislatures should be representative governments and, as democratic institutions, be inclusive to the people that they serve, especially those who have historically been excluded from the policymaking process.

Community Outreach

For federal funds to be utilized in an inclusive manner, the public must be aware of how they can best access these funds. It takes greater effort to reach some community members, but this should not be seen as an intractable issue. States can build distribution and information networks that prioritize inclusivity. For example, a Center for Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) report on antiracist equitable responses to COVID-19 included recommendations on the use of ARP funds to develop a robust public outreach operation, including:

-

Launch a public awareness campaign that includes a centralized, one-stop-shop webpage at which people can learn about the various kinds of supports for which they may be eligible. The campaign should also include media outreach in languages targeted to particular communities and engage community-based groups in helping raise awareness and in directing people to the centralized site. States can also prioritize working with telephone and online “helplines,” which can connect people to resources they may not otherwise know about.

-

Convene and train organizations that already help people access SNAP, Medicaid, or other supports. The state can make these groups aware of the various forms of assistance now available and provide them with tools and resources such as outreach materials and directories of places people can go to get help. A key goal of these efforts should be to build more destinations around communities where people can learn about the full range of supports and how to get them. States should also train their own staff across a range of programs so that they can connect a person applying for one form of assistance to other supports for which they may be eligible.

-

Fund organizations that are well positioned to reach people with particularly significant barriers to accessing support, including immigrants and people of color with low incomes. States can provide outreach funds to community organizations—such as community action agencies, faith-based organizations, and grassroots organizations—that are most familiar with the needs of people in their communities as well as the resources available to help them. Funded groups should have the trust of their target communities and mechanisms in place for regularly communicating with the intended audience. They can use these mechanisms to build awareness and, in some cases, offer assistance with applications or with navigating other systems of support.

With Pennsylvania getting about $7.3 billion in federal funds from the American Rescue Plan, local community advocates worked with state legislators to help develop a progressive Pennsylvania Rescue Plan in 2021, which includes investments in a range of supports for communities, including local jobs, schools, child care, internet and infrastructure, public health, clean energy, direct care workers, telehealth, research and innovation, housing and rental tax relief, affordable housing, essential workers, paid sick and family leave, community college and career training, unemployment benefits, and retirement savings.

SiX played an active role in ensuring this plan would reflect the needs of Pennsylvanians. SiX supported a series of town halls, listening tours, and press events put on by state legislators. Feedback from the public made it clear that a practical need existed for legislators and advocates to help individuals and families to even access ARP funds.

In response, SiX quickly created a website to help Pennsylvanians access ARP benefits. With this website, advocates and state legislators were able to help their communities to better understand eligibility for expanded funds, and to access ARP funds, reaching over 11,500 Pennsylvania residents. The website also helped demonstrate a connection and impact between the broader public policy recommendations and their individual lives. This process has had the added benefit of improving a number of the state legislators’ commitment to working with local advocates and to finding creative ways to connect their work with their communities.

The federal IIJA provides new opportunities for states to prioritize inclusiveness in both the planning of and benefits from these federal funds. The Biden administration has taken steps to encourage state spending of federal infrastructure dollars to benefit historically disadvantaged communities, such as through Federal Executive Order 14008, which created the Justice40 Initiative to order relevant state agencies to “jointly publish recommendations on how certain Federal investments might be made toward a goal that 40 percent of the overall benefits flow to disadvantaged communities.” After the IIJA was enacted, President Biden issued Federal Executive Order 14052, on the implementation of IIJA, and it states that implementation priorities must include “investing public dollars equitably, including through the Justice40 Initiative, which is a Government-wide effort toward a goal that 40 percent of the overall benefits from Federal investments in climate and clean energy flow to disadvantaged communities.”

While states are not required to follow the goals of the federal Justice40 Initiative, California legislators have introduced a bill (2022 CA AB 2419) to not only align state infrastructure spending from the IIJA with this goal, but to also go beyond it by requiring a state agency administering federal funds to “allocate a minimum of 40 percent of those funds to projects that provide direct benefits to disadvantaged communities and disadvantaged unincorporated communities in the state” and “a minimum of an additional 10 percent of those funds to projects that provide direct benefits to low-income households in the state or to projects that provide direct benefits to low-income communities in the state.” In order to actualize these goals, the legislation would create a state Justice40 Advisory Committee to “identify infrastructure deficiencies” in disadvantaged and low-income communities and to recommend infrastructure projects to address these deficiencies as well as agency guidelines to “achieve better climate, labor, and equity outcomes.”

What’s more, this advisory committee is clearly designed to be inclusive of historically excluded voices, as it would be made up of representatives of a Native American tribal community, a local/regional group working on environmental issues affecting frontline communities, a local/regional transportation equity group, an environmental justice organization, an equity- or racial justice-focused group, a local/regional group working with a low-income community, a public sector labor union, and a labor union that represents the building and construction trades.

Accessible and Collaborative

State legislatures should be accessible to the public and adopt institutional policies, rules, and practices that share the institution’s power with communities, especially those that have historically been excluded from the policymaking process. To reach historically excluded communities, policymakers need to engage new communications tools and forge relationships that validate them as trusted and valued partners and to collaborate with established community-based organizations, which can provide stewardship and longevity with community relationships.

Participatory Budgeting

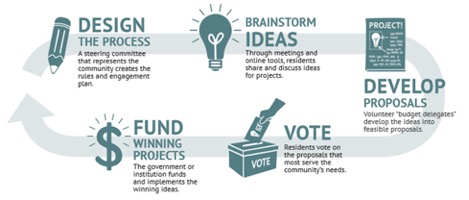

When exploring community and government collaboration on how best to use public funds, one example that is likely to be brought up is participatory budgeting. Participatory budgeting is a process that involves the community in identifying, developing, and selecting funding proposals. As a 2016 Hawaii House Resolution put it: Though each participatory budgeting process may be different, most follow a similar pattern where residents brainstorm public spending ideas and priorities, volunteer delegates develop proposals based on these ideas, residents vote on the proposals, and public agencies implement the top proposals. This graphic from the People Powered Hub provides a basic illustration of how participatory budgeting could work:

An article in the Journal of Urban Health described how participatory budgeting could diminish health disparities and support civic engagement. Some of these benefits could also support policy feedback loops, where the policy itself changes the political conditions and impacts future policymaking (see sidebar for more).

-

In particular, political participation and civic engagement can promote individuals’ psychological empowerment—that is, residents can gain a greater sense of personal and collective efficacy, including the feeling that they can make a difference in their communities …

-

Residents can develop greater civic skills, civic knowledge, and social and political awareness.

-

Research into US PB [participatory budgeting] so far has shown high voter turnout among lower income residents and people of color in many PB communities …

-

PB could strengthen CBOs [community-based organizations] by providing a context for organizations to meet and collaborate, and thus to build stronger ties among themselves and to improve their relationships with government. Those new relationships could in turn facilitate CBOs’ ability to collectively advocate for policy changes that would help reduce health inequalities.

-

PB can raise awareness of community needs that may be forgotten or invisible under politics-as-usual.

-

If project ideas that benefit people of greatest need make it onto a PB ballot and win, PB could lead to a more equitable distribution of public funds than what would have been funded without PB.

-

Even if projects of greatest need do not end up winning the PB vote, they may nevertheless inform elected officials’ spending priorities elsewhere.

Participatory budgeting has primarily been implemented at the local level, such as in New York City, which created a civic engagement commission to develop participatory budgeting (See: NYC Charter 4 Chapter 76: Civic Engagement Commission, created by 2018 NYC Ballot Measure on Civic Engagement Commission, or 2018 NYC Local Law 211).

Attempts at establishing statewide programs have thus far failed, such as an Ohio bill introduced in 2018 (OH HB 653), which would have created a participatory budgeting fund to provide a predetermined amount of money to county governments for the cost of public projects submitted by the public and approved through a local voter referendum process. In order to receive these funds, a county would have been required to: (1) oversee the county's participatory budgeting process; (2) establish a process under which members of the public may submit project proposals; (3) hold public hearings to consider the proposals; and (4) select the proposals for submission to the electors.

Recent federal funding has provided new opportunities to pilot participatory budgeting. For example, Oregon legislators allocated American Rescue Plan Act (ARP) funds to launch Youth Voice, Youth Vote PB in 2022, which provides a collaborative process for youth and their families to help allocate $500K in COVID-19 relief funds.

Listening Tours

If a formal or pilot participatory budgeting process is not feasible, state policymakers can still prioritize accessibility and collaboration by engaging in ongoing listening tours around their state that address both immediate and long-term community needs. For example, the Rhode Island Governor’s Office coordinated a series of meetings with community members throughout the state in order to develop their state’s recovery plan. If done well, listening tours can surface key issues and create pathways for authentic dialogue between community members and their representatives. But in order to do so, policymakers must embrace community members as the true experts on how best to support their communities, and lift up the voices of those most impacted—those closest to the pain should be closest to the power.

Colorado ARP Listening Tour

For example, as part of the ARP planning process, a bipartisan group of Colorado leaders from the executive and legislative branch held a listening tour of public meetings across the state to hear from a diverse set of communities, businesses, and other stakeholders. This resulted in the creation of a report synthesizing the ideas heard, which fell into three broad categories:

-

Recovery & Stimulus: These ideas ranged from incentives to employers for hiring or rehiring and a wide variety of infrastructure construction projects to promotion of Colorado’s conference centers, tourism destinations, and restaurants and direct relief to families and individuals struggling to meet financial challenges or find employment.

-

Systemic Transformation: These ideas included a comprehensive transformation of education from early childhood through K-12 and higher education, making major investments in multimodal transportation, and significant investment to relieve Colorado’s housing crunch particularly to address affordable housing and disparities in home ownership.

-

Budget & Programmatic Gaps: Numerous participants raised concerns about the ability to adequately fund a variety of programs ranging from behavioral and mental health to community economic transitions, transportation infrastructure and support for homeless populations and transitions.

Accountable and Transparent

State legislatures should have the public’s trust as institutions that uphold ethical and democratic standards of governance, and are accountable to the community, especially those most impacted by public policies and programs.

Performance-Based Budgeting

Accountability requires that policymakers set goals and gather data to measure progress toward those goals, and this process must be fully transparent to impacted stakeholders and the public at large. One important and initial step is to ensure that fiscal notes and other fiscal planning tools are timely and accessible. Similarly, transparency and accountability have been a central theme of good government initiatives such as performance-based budgeting.

Performance-based budgeting has been used by the states since at least the 1970s (see Tennessee example), and states like New Mexico have demonstrated how a “Legislating for Results” framework can be used by a state’s legislative finance committee to design evidence-based budgets. While over 30 states use performance-based budgeting for at least higher education funding, a relatively new movement is underway to move from outcomes-based budgeting to equity-based budgeting.

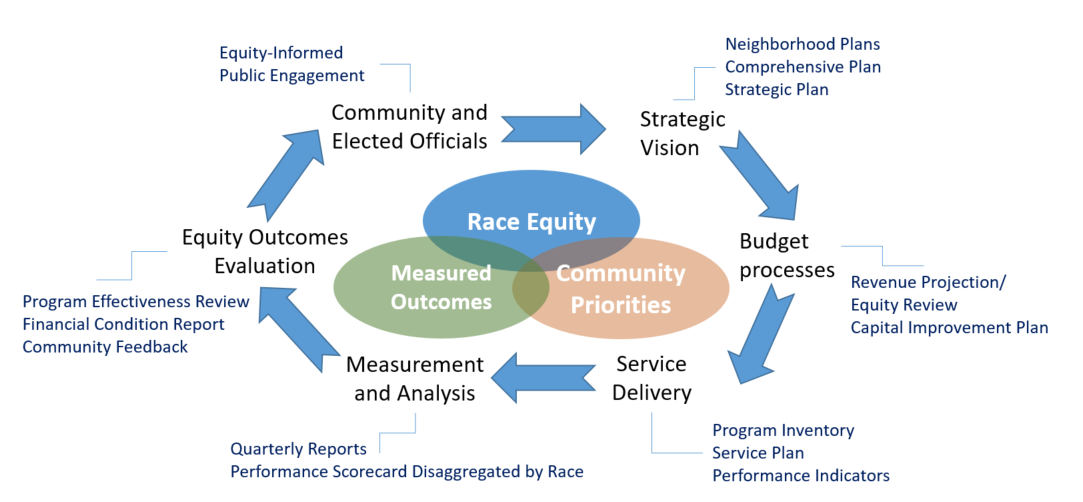

An article from the Metropolitan Planning Council in Chicago explains how “budgeting for outcomes” could instead become “budgeting for equity” by including the following key activities through a race equity lens: (1) determine community outcomes through a robust community engagement process; (2) forecast expected revenues and their distributional impact; (3) allocate revenues to priorities based on strategic discussions with stakeholders; and (4) develop performance measures that include impacts disaggregated by race. The article provides the following graphic to demonstrate how this could translate at the local level:

An article produced by FUSE Corps, in partnership with the Government Alliance on Race and Equity (GARE), highlighted “seven ways to bring an equity lens when prioritizing government budgets”: (1) clearly define “equity” so that a common language/terminology is shared across agencies; (2) drill down into the numbers to expose inequities, potentially using a targeted universalism approach; (3) use data as evidence to hold officials accountable; (4) track and keep assessing the success of investments in equity; (5) include the voices of diverse communities in budget discussions; (6) take a high-level view of funds for greater equity by taking a system-wide approach to “build equity across the entire budget when making decisions;” and (7) find creative ways to simplify delivering funds.

Virginia Smart Scale

One example of equity-based budgeting is a Virginia system to analyze transportation and infrastructure spending options. Virginia’s legislature unanimously passed 2014 VA HB 2 (Chapter 726), which directed the Commonwealth Transportation Board (CTB) to develop and use a prioritization process to select transportation projects and ensure the best use of limited tax dollars. The bill led the CTB to develop SMART SCALE, a data-driven system that scores projects based on an objective, outcome-based process that is transparent to the public. Factor areas include safety, congestion mitigation, environmental quality, economic development, land use, and accessibility. “Accessibility” considers projects that will ensure access to jobs for disadvantaged groups, which includes low-income, minority, or limited-English proficiency populations. The results from the screening process are presented to the public, and the CTB takes public comments into account when selecting transportation projects.

Oversight

Failure to prioritize transparency and accountability through oversight increases the risk of fraud. Websites that track information about taxpayer-funded projects ensures that members of the public can be engaged in the process, while also allowing stakeholders, such as journalists or competitors that submit bids for projects, to raise concerns about potential fraud. This will be of critical concern when considering oversight of funds received through the recently enacted Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA). The Coalition for Integrity’s report titled “Oversight of Infrastructure Spending” lays out a number of recommendations to increase IIJA transparency and accountability, including:

-

Creation of a public website to track infrastructure spending

-

Opportunities for community interaction and participation in infrastructure discourse

-

Conflict-of-interest disclosures from state officials and fund recipients

-

Proactive audits by relevant state auditors/agencies

-

Additional funding for state agency oversight

-

Whistleblower protections

-

Interagency task forces to investigate corruption

Oversight also means enforcing current laws, such as Title VI of the Civil Rights Act which requires that programs receiving Federal financial assistance do not exclude from participation in, deny the benefits of, or otherwise discriminate against an individual based on race, color, or national origin.

Responsive and Effective

State governments should be responsive to community needs and maximize resources across agencies in partnership with stakeholders to ensure that policies are implemented effectively and with fidelity.

Multi-Stakeholder Coordination

Coordination between state agencies is critical to a state’s ability to effectively coordinate federal funds and to quickly respond to community needs. For example, a number of governors have already established cabinet- or subcabinet-level cross-agency coordinating bodies to better implement the IIJA, including in Kansas, Maryland, Michigan, and Oregon. The need for a coordinated multi-stakeholder rapid response is also abundantly clear when multiple state and local agencies are tasked with responding to crises that touch communities across lines, including the pandemic, or natural emergencies, etc.

A 2021 report from National Academy for State Health Policy (NASHP) examined Illinois, Indiana, and Rhode Island’s pandemic response, including their use of new and existing funding sources, and found that “cross-agency partnerships, as well as those with local entities and community-based organizations, have been important for determining how to strategically invest new federal dollars.” This report provides examples of multi-stakeholder coordination around federal funds, including the use of CARES Act funding in Illinois to support multiple state agencies and community partners and ARP funding in Indiana to establish a new unit of government to combine multiple funding streams for the support of the state’s human services system.

Nevada Office of Federal Assistance

Another example of cross-agency system alignment has been created through a recent Nevada law, 2021 NV AB 445, which establishes the Office of Federal Assistance (OFA) within the Governor’s Office. The OFA is tasked with developing a state plan to maximize federal assistance and share the plan online with the public. This plan must identify methods for “expanding opportunities for obtaining federal assistance, including … expanding opportunities for obtaining matching funds for federal assistance through the Nevada Grant Matching Program”; “streamlining process, regulatory, structural and other barriers … at each level of federal, state or local government”; and “effective administration of grants, including … best practices relating to indirect cost allocation.” As the stakeholders closest to the community often have a better sense of what the community needs are, this law both requires the OFA plan to examine better ways to coordinate between state and local agencies, tribal governments, and nonprofit stakeholders, and it also creates a grant matching program so that these stakeholders can increase access to federal grants that require a match. State grants are prioritized for projects that “address the needs of underserved or frontier communities.”

Using Agency Enforcement Powers to Protect Worker Rights

A stated goal of many federal funding initiatives is the creation of “good” jobs. This shows up prominently in the American Rescue Plan (ARP) and the recent infrastructure law.

However, in order to be effective at reaching this goal, state legislatures must pass laws that ensure labor rights and protections, and agencies must play a key role in enforcing these laws and regulations. For example, much of the federal funding received by the states through the recent infrastructure law will require Davis-Bacon prevailing wages, but this does not cover all of the federal funding, and federal labor protections only establish a floor. States with stronger labor enforcement powers will be better positioned to address wage and hour violations, including the various forms of wage theft.

The Center for Innovation in Worker Organization (CIWO) at Rutgers University has created a Labor Standards Enforcement Toolbox, which includes best practices on topics such as taking complaints, conducting investigations, collecting owed wages, practicing strategic enforcement, preventing retaliation, particularly for immigrant workers, and agency partnerships with community organizations. The CIWO report on working with community organizations is especially illustrative as it includes co-enforcement, which is another way to connect with the community.

Co-enforcement of labor standards is an enforcement model wherein agencies target specific, high risk sectors and partner with organizations that have industry expertise and relationships with vulnerable workers. Due to relationships of trust and power, enforcement agencies, workers, worker organizations, and employers each have unique attributes that are not interchangeable:

-

Agencies are endowed with the power to set standards, incentivize behavior, compel compliance, and legitimize claims;

-

Workers bring firsthand experience of working conditions and employer practices, and have relationships with other workers and supervisors;

-

Community and worker organizations have reputational credibility giving them access to vulnerable workers and information on problematic firms and industries, as well as access to tools for compelling compliance that may not be politically feasible for agencies;

-

High road employers can establish best practices and work together to report unfair competition.

Equity-focused

State legislatures should dismantle systems of oppression that have been enshrined in public policy and advance policies that prioritize equity for historically marginalized and exploited communities.

Oregon Coordinated Care Organizations

Medicaid is the largest source of federal funding for states, accounting for 45 percent of all federal fund expenditures by states, and 27 percent of all state spending in 2021. In total, states received $222 billion in federal Medicaid funds and an additional $18 billion in Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) block grants. In Oregon, leaders have pioneered equity-centered innovations in the state’s Medicaid program to strengthen health insurance coverage for its low-income residents.

Oregon lawmakers launched the state’s health care transformation in 2011 (2011 OR HB 3650), directing the state Medicaid agency, the Oregon Health Authority (OHA), to seek federal approval for a section 1115 waiver demonstration project, which allows states to undertake experimental, pilot, or demonstration projects in their Medicaid programs while being waived from certain requirements for the use of federal Medicaid funds. The legislature approved (2012 OR SB 1580) the OHA waiver proposal in the following year, which was approved by federal officials and renewed again in 2017.

Oregon’s model centers community and equity in the provision of integrated health care to Medicaid enrollees. A coordinated care organization (CCO) “is a network of all types of health care providers (physical health care, addictions and mental health care) who have agreed to work together in their local communities” to serve Medicaid beneficiaries. Unlike the traditional model of Medicaid managed care, where private managed care organizations (MCOs) contracted by the state to provide coverage are primarily driven by cost reduction, CCOs are accountable to improved health outcomes in the communities they serve. Some of the equity-focused features of Oregon’s CCOs include:

-

Community corporate governance. By statute, CCOs must be local, community-based organizations or statewide organizations with community-based governance structures, and must include at least two members who are current or former Medicaid enrollees (Or. Rev. Stat. § 414.572). By contrast, large multi-state firms dominate the managed care industry, with just six firms accounting for 51 percent of all MCO enrollees nationwide.

-

Community- and consumer-led strategic planning. CCOs are required to convene community advisory councils (CACs) to oversee the development and adoption of a community health improvement plan to serve as a strategic plan for the CCO in improving the health outcomes of the community it serves (Or. Rev. Stat. § 414.575). Consumers or consumer representatives must constitute a majority of the membership of the CAC, and the OHA provides resources and funding to support the work of CACs.

-

Addressing the social determinants of health. CCOs are authorized to cover non-medical health-related services that address the social determinants of health. These benefits include flexible services for individual members like housing supports or transportation services, as well as community-level health interventions that may benefit non-members, such as supporting green infrastructure investments in low-income neighborhoods or partnerships with other organizations to provide training or education to communities.

-

Value-based payment. Oregon also adopted a value-based payment model, which incentivizes CCO performance based on health metrics. Under this model, CCOs receive bonuses based on a set of incentive metrics like meaningful language access to culturally responsive health care services, timeliness of postpartum care, and child and adolescent well-visits.

-

Community reinvestment. In 2018, Oregon legislators enacted a bill (2018 OR HB 4018, later amended by 2019 OR SB 1041) requiring that a portion of net profits for CCOs be reinvested back into their communities to address health inequities and the social determinants of health and equity based on the community health improvement plan developed by the CAC. In 2021, CCOs across the state collectively reinvested millions of dollars into a wide range of activities, including housing and homelessness supports, expanding bike lanes and trails, and mental health crisis services. During the same year, the five largest MCO firms in the country raked in over $51 billion in profits as Medicaid enrollment increased during the pandemic.

Innovative

State legislatures should advance policies that improve peoples’ lives and strengthen communities. Innovation allows governments to experiment with new policy solutions to pressing issues faced by local communities.

Maryland Climate Resilience

The urgent threat of climate change is universal, but communities have unique needs that may require a local or regional response. Billions of federal funds for climate adaptation and resilience are available to governments and other eligible entities, and billions more have been allocated recently in the federal Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA). Maryland lawmakers have passed a slate of legislation aimed at developing a dynamic plan to develop the state’s climate resilience at the community level, with state support and coordination:

-

Local and regional climate resilience authorities. In 2020, the Maryland General Assembly passed a bill (2020 MD SB 457) to allow local governments to solely or jointly establish resilience authorities, a quasi-governmental agency authorized to receive public and private funding to finance, manage, and support infrastructure projects to mitigate the effects of climate change. To date, several local resilience authorities have already begun the process of identifying and executing resilience projects.

-

State climate resilience funding. The following year, the General Assembly enacted the Resilient Maryland Revolving Loan Fund (2021 MD SB 901) to provide low- or no-interest loans to local governments and nonprofits for local resilience projects.

-

Centralized climate resilience expertise. In 2022, the General Assembly established the Office of Resilience, led by an appointed Chief Resilience Officer (2022 MD SB 630). The new office is responsible for coordinating federal, state, and private funding and technical assistance to support resilience efforts and administering state climate mitigation grants and loans, among other duties.

By building an intergovernmental framework for climate resilience, Maryland lawmakers provided state resources and expertise to support local communities in successfully navigating the complexities of the billions in federal climate resiliency funds, and also created flexible pathways for these communities to mitigate the harms of climate change.

Transformative Climate Communities (TCC)

2016 CA AB 2722 (Chapter 371) established the Transformative Climate Communities (TCC) Program to “fund the development and implementation of neighborhood-level transformative climate community plans that include multiple, coordinated greenhouse gas emissions reduction projects that provide local economic, environmental, and health benefits to disadvantaged communities …”. The CA Strategic Growth Council (SGC), which administers the TCC Program, supports community-driven, data-driven, transformative strategies to achieve the community’s vision.

The TCC Model prioritizes equity by making sure that proposals are designed with local residents’ and stakeholders’ needs in mind; include a range of community, business, and local government stakeholders, who collaboratively develop a shared vision of community transformation; and protect the current community by taking steps to avoid displacing existing residents and local businesses. A TCC goal is to make sure that those in the community own the changes and reap the benefits of the state’s investments.

Since 2018, the CA SGC has awarded over $230 million in TCC grants to 26 communities, and with the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, the TCC model can be a powerful force multiplier for disadvantaged communities by catalyzing local, multi-sector partnerships that leverage private and public funds to sustain community revitalization and equitable development.

To this end, in 2022, SGC launched an online Model Hub, which draws on TCC and other SGC programs to provide tested policy models, case studies, and exportable templates to support program administrators and funders in addressing disparities and equitably investing in under-resourced communities. Dream.org is launching a pilot program based on TCC to empower frontline communities to unlock historic amounts of climate funding from the Inflation Reduction Act to ensure that communities most impacted by climate change are the first to benefit from these funds.